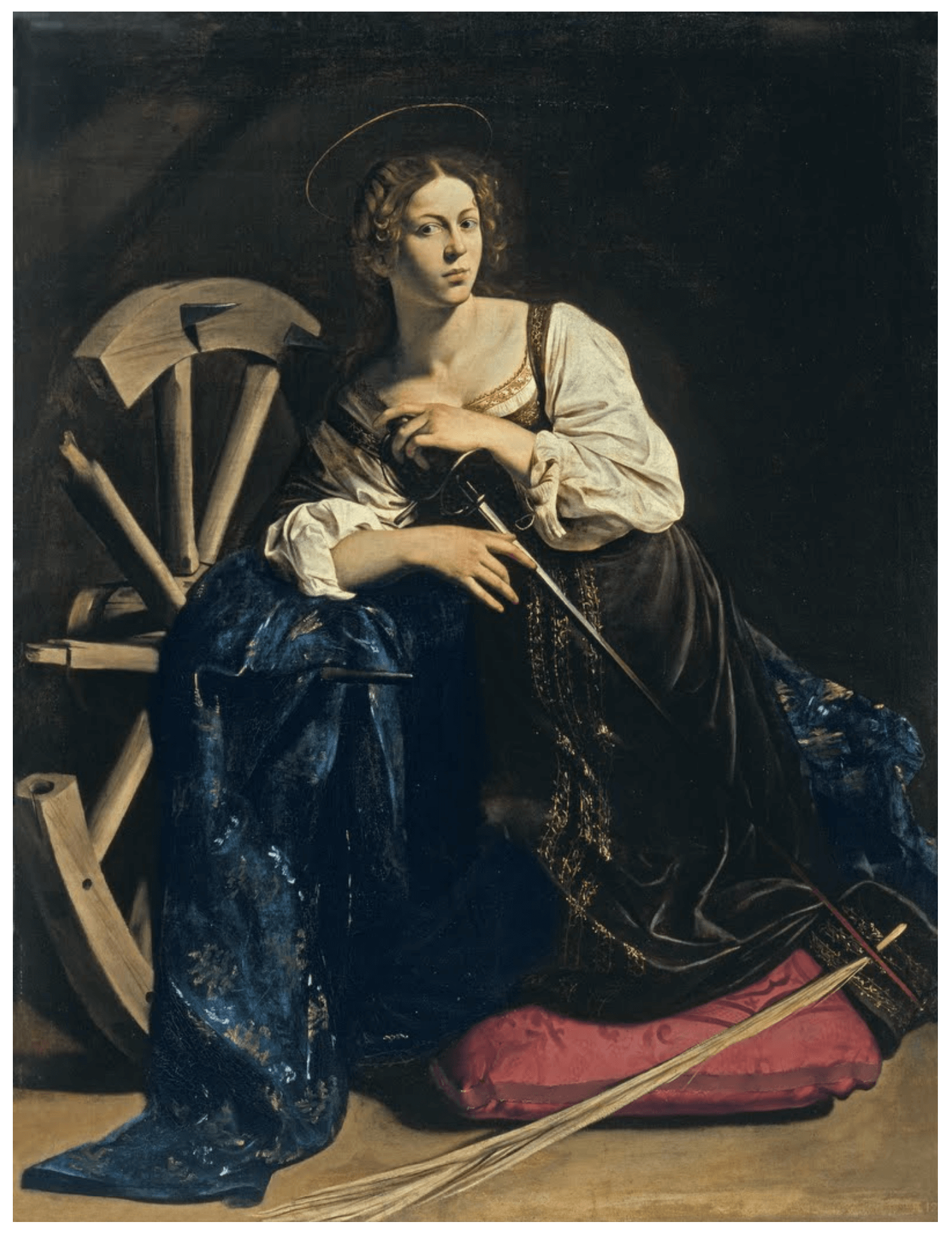

St Catherine’s feast day today… Painted during the artist’s time in Rome, this picture features familiar elements of Saint Catherine’s life: the wheel, the sword with which she was beheaded, the martyr’s palm, as well as a lovely red cushion. I love the playful geometry of the diagonals – like visible polyphony (good name for a band!) – and the light on the texture of her robes quietly ennobles both her and the canvas. Compare this with Raphael’s picture of the same saint, around 90 years older: Caravaggio’s Catherine is far from a pious, transfigured Renaissance saint. She is real: challenging and bold, flesh and blood, not fearful of death here, even leaning defiantly towards the machinery of her torture. Look at the way the light bursts her out of the sepulchral darkness behind her. This is all radical enough in 1598, but there’s more. The real-life model was Fillide Melandroni, one of Rome’s best-known prostitutes at the time, who is a frequent guest in some of his other paintings, too. (You might infer his interest in her was not purely professional; I couldn’t possibly comment.) It seems possible that a dispute about Melandroni was what led to Caravaggio’s murder of Ranuccio Tomassoni, in a duel in 1606. Here is the extraordinary intersection of religious imagery and brutal events, bringing the antique narrative of St Catherine crashing into Caravaggio’s own autobiographical reality. (This is how and why the distance between life and artistic subject is diminished: Raphael’s pedestal might elevate the saint, but gives her no room to move). Caravaggio’s Catherine is a woman first, then a saint. No surprise, therefore, that Caravaggio provocatively casts a real sinner as a saint – the last shall be first etc – and reminds us that human life is rooted in conflict: we are all of us somewhere perilous between good and bad, fortune and misfortune, fortitude and weakness.

Drowning Dog – Goya

Drowning Dog – Goya